Drug-Impaired Driving Threatens Road Safety

The deadly toll of drug-impaired driving in the USA keeps climbing, with a stark 7.4% increase in drug-involved crash fatalities from 9,140 in 2016 to 9,818 in 2020.[1] The scope of the problem is massive – in 2021 alone, 13.6 million people admitted to driving under the influence of illicit drugs. When seriously or fatally injured drivers were tested after crashes, more than half (56%) had drugs in their system.[2]

For the first time in United States history, driving under the influence of drugs has surpassed driving under the influence of alcohol.

See: https://www.ghsa.org/resources/drugged-driving-2017

Troubling is also how the nature of this crisis is shifting. New data reveals that cannabis could be overtaking alcohol as the leading threat on US roads. Long-term research tracking fatal crashes shows cannabis-involved deaths surged from 9% to 21.5% between 2000 and 2018. During the same period, fatal crashes involving both cannabis and alcohol more than doubled from 4.8% to 10.3%.[3] As recreational cannabis becomes legal in more jurisdictions – as of November 2024, 24 states have legalized cannabis personal use for adults[4] – law enforcement faces a growing challenge: polysubstance-impaired driving. Here the challenge lies not only in the complexity of detecting cannabis impairment but also in the fact that individuals who are identified as alcohol-impaired drivers are often not further investigated for potential drug use.[5]

Law Enforcement Struggle with Drug-Impaired Detection

Unlike alcohol detection, which has firmly established standard roadside tests and procedures,[6] law enforcement lacks reliable screening tools to identify drug-impaired driving. SFSTs, highly effective for alcohol detection, are inadequate for detecting drug impairment.[7] While specialized Drug Recognition Experts (DREs) can help, their training is expensive and time-consuming, resulting in too few qualified officers on the streets. Further complicating matters, many police officers tend not to prioritize drug-driving cases.[8]

When officers suspect drug-impaired driving, the path to gathering evidence is complex. While implied consent laws allow officers to request chemical tests (for alcohol and/or other drugs), drivers can legally refuse – though they may face penalties.[9] Significant practical challenges emerge for drivers who agree to testing. Blood draws require a warrant (and usually medical personnel),[10] and urine tests demand same-gender observation to prevent tampering—a requirement that has become more nuanced with fluid gender identities. Both options require trips to specialised facilities, creating critical delays. These delays pose a serious problem for the prosecution. By the time testing occurs the body may have already metabolized the drugs, weakening the evidence. THC poses a particular challenge, as blood and urine tests cannot reliably distinguish between recent use and past consumption – crucial information for determining impairment at the time of driving.[11]

The legal landscape adds another layer of complexity. States have varied laws on drug-impaired driving,[12] especially regarding cannabis,[13] causing inconsistency in protocols and uniform standards. Some states enforce impairment laws only; others enforce per se laws. Some States allow oral testing to be included in their implied consent laws, while others do not. These inconsistent laws and incomplete detection methods leave officers poorly equipped to tackle a mounting public safety crisis.

Law Enforcement Employs Oral Fluid Field Screening (OFFS)

Oral Fluid Field Screening (OFFS) is gaining momentum in the United States, driven by cannabis legalization and the opioid epidemic. While OFFS has been successfully implemented in many countries.[14] The U.S. has been catching up with this roadside drug testing method since its 2004 debut in Victoria, Australia. What follows below are often-asked questions regarding OFFS in the USA.

How do police include OFFS in their drug-driving investigation?

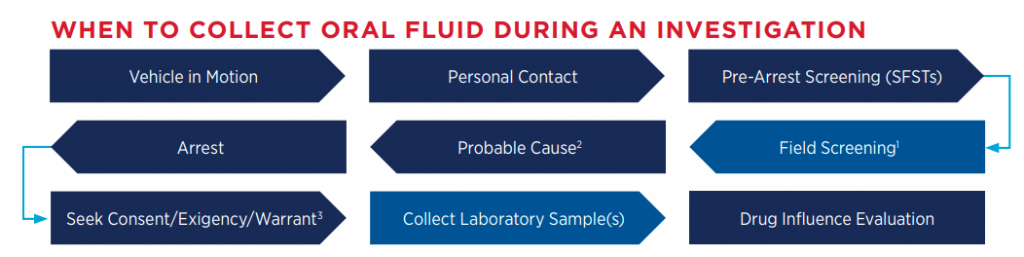

On the roads, law enforcement uses oral fluid in two key ways: (1) using OF devices, which deliver rapid positive/negative results, which helps establish probable cause for arrests, followed by confirmatory blood or OF tests; (2) collecting oral fluid for laboratory confirmation analysis, which helps with a more accurate drug identification by minimizing delays and preserving evidence before blood is drawn.[15]

Picture from “Using Oral Fluid to Detect Drugs. Infographics. Sponsored by AAA. 2024.”[16]

What is the legislation policy for the use of OFFS?

Policy approaches vary from state to state. As of 2024, Michigan and potentially Minnesota (see below) have formed separate legislation to authorize preliminary OFFS, in parity with preliminary breath testing. 16 States have included OF in their implied consent laws (i.e., Indiana). In comparison, 6 states have authorized OF collection by an impaired driving statute only (i.e., Arizona), and 1 state (Alabama) authorised both in its implied consent law. 1 state (Delaware) authorized OF for under +21. The rest of the States do not have explicit oral fluid collection laws, but many of them have tried it on a pilot basis (Vermont, North Dakota).[17]

In the US, there are 4 pathways leading to implementing pilot programs for OFFS. Pilot programs can be:

1. Established via legislation and funded by the State Legislature (Michigan and Minnesota).

2. Established by a State Agency (e.g., forensic laboratory) in coordination with law enforcement agencies and other partners (Alabama).

3. Established and funded by a State Highway Safety Office (program implemented by Law Enforcement Agencies) (Arizona, Indiana)

4, Launched by a Law Enforcement Agency (California, Illinois, Montana).[18]

Today, Michigan, Indiana, and Alabama run statewide OFFS.[19] Other jurisdictions have tried the new technology as a local, county, or agency pilot test to assess whether OF technology is reliable in detection and can reduce delays in collecting blood samples or inconveniences stemming from urine testing. paired drivers.

Which U.S. Jurisdictions use OFFS

Michigan was the first state (in 2017 and 2019) to require drivers to submit to OFFS as part of drug-driving investigations.[20] Today, states’ DRE officers are allowed to require a person to submit to a preliminary oral fluid analysis as one of many tools in their drug-driving investigations. If the driver refuses, it is a civil infraction that results in the issuance of a 24-hour out-of-service order (MCL 257.625r (6) to (9)).[21]

Minnesota is taking significant steps to address drug-impaired driving enforcement challenges, particularly following cannabis legalization (2023). In 2022, the state proposed amendments to drug-driving legislation (Proposal 2854)[22]In 2024, the Office of Traffic Safety (OTS) and Minnesota State Patrol launched a pilot project to test oral fluid screening devices as new enforcement tools.[23] The pilot project aims to evaluate whether these roadside instruments can effectively support DREs’ observations of impairment and guide driver processing procedures. Upon completion, OTS will report findings to the Minnesota Legislature and, if successful, request approval to implement these devices as screening tools, similar to how preliminary breath tests are used for alcohol enforcement.[24]

Unlike Michigan and Minnesota, Indiana did not launch a pilot study. Still, the Indiana Criminal Justice Institute (ICJI) decided to fully implement the program in 2020 in partnership with the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Office, equipping DREs and other police officers statewide.[25] In 2021, as part of the state’s ongoing efforts to reduce drugged driving and traffic fatalities, ICJI distributed almost 100 OF mobile test system units to 19 agencies in the region.[26] In Indiana, OF testing is subject to implied consent laws, and refusal results in penalties. A first refusal can result in a one-year license suspension, while a second or subsequent refusal within five years can lead to a two-year suspension.[27]

Alabama, after its pilot program (2017), transitioned to a permanent Oral Fluid Drug Testing program at the State Crime Laboratory level, including both (1) screening at the roadside and (2) evidentiary confirmation oral fluid drug testing at the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences (ADFS). Field screening tests for six major drug categories (marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine, amphetamine, opioids, and benzodiazepines) and provide immediate positive/negative results to establish probable cause, similar to alcohol PBTs. For evidentiary purposes, after an arrest, OF is collected for the state laboratory to conduct confirmatory testing for approximately 30 different drugs, with samples collected using ADFS-provided kits.[28] Alabama is the only state with screening and evidentiary oral fluid testing. This is possible because ADFS has the authority to amend rules on chemical testing (in 2018) and because OF tests are subject to implied consent (SB258 in 2021). That means drivers who refuse the test after an arrest are subject to automatic driver’s license suspension, just like those who refuse the post-arrest breath test.[29] Since implementation in August 2018 through July 2024, the program has processed over 2,500 cases and led to successful court testimony. Law enforcement agencies are responsible for purchasing and maintaining the roadside devices, while the state provides specimen collection kits containing oral fluid devices and blood tubes. [30]

North Dakota is the most current state that, in 2024, started using an approved oral screening device as a preliminary tool for detecting drug impairment after an initial oral fluid testing pilot study (2022-23) supported by the state and the Oral Fluid Technical Advisory Committee.[31]

Many will follow.

Take Away Message

In Indiana, for instance, over 3,000 OF tests had been conducted as of 2024, increasing drug influence evaluations and sending more blood samples for lab analysis. This has led to more arrests for drug-impaired driving as the state has intensified its focus on combating this issue. In 2023, fatal crashes dropped by approximately 10% compared to the previous year, reflecting the program’s success in enhancing road safety.

See: https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/indiana-oral-fluid-testing-impaired-drivers/

Roadside oral fluid screening is transforming how law enforcement addresses drug-impaired driving. Many US jurisdictions have successfully implemented OF testing programs, proving they are an urgent detection and deterrent strategy because they can provide a snapshot of drugs present in the system during observed impaired behaviour. Even in US States where OF programs were not legally supported (Vermont 2020),[32] there is evidence of its usefulness when it comes to road safety.[33]

One issue with OFFS might be that, by law, unlike evidentiary blood tests, OFFS results are not admissible as evidence in court. Another issue might be their reliability.[34] For example, jurisdictions with “per se” drug driving statutes (the presence of a drug creates a DUID violation, regardless of the impairment tests) might have officers make unjust arrests based solely on the results of a screening test. In both cases, we have to keep in mind that police should use OF devices only as an additional tool in their comprehensive drug-droving investigation while pursuing ongoing efforts to improve enforcement and reduce fatalities related to impaired driving.

For jurisdictions considering implementing the OFFS program, the National Alliance to Stop Impaired Driving (NASID), in collaboration with RESPONSIBILITY.OR[35] offers a comprehensive collection of oral fluid resources, including scientific literature and reports supporting the use of oral fluid for drug testing in roadside and laboratory DUID investigations. Insights from states with pilot programs and access to program websites are available. Additionally, there are policy resources to aid in legislative changes for oral fluid use and address legal concerns.

[1] Chen, K. L., Tsai, B.-W., Fortin, G., & Cooper, J. F. (2022). TRAFFIC SAFETY FACTS Drug-Involved Driving. https://safetrec.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/publications/safetrecfactsdrug_involveddriving_2022.pdf

[2] https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/drug-impaired-driving-contribution-emerging-and-undertested-drugs

[3] Lira, M. C., Heeren, T. C., Buczek, M., Blanchette, J. G., Smart, R., Pacula, R. L., & Naimi, T. S. (2021). Trends in Cannabis Involvement and Risk of Alcohol Involvement in Motor Vehicle Crash Fatalities in the United States, 2000‒2018. American Journal of Public Health, 111(11), 1976-1985. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2021.306466

[4] https://www.mpp.org/issues/legislation/key-marijuana-policy-reform/

[5] https://nasid.org/better-dui-detection/

[6] Field testing, such as Standardized Field Sobriety Testing (SFST), which assesses an individual’s physical and cognitive abilities, and (2) breath tests, which can determine the presence of alcohol in the body, as there are clear breath and blood alcohol limits that can be measured.

[7] https://www.ncsc.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/1580/sjc-ncsc-ebjdm-dui-11-19-18.ashx.pdf

[8] Wise, I. (2024). The Use of Oral Fluid Samples to Test for Driving Under the Influence of Marijuana. Georgia Criminal Law Review, 2(1). https://doi.org/https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/gclr/vol2/iss1/4

[9] “Implied consent” laws are enforced in all US states. The law provides “that anyone driving a vehicle in the state has automatically consented to a chemical test if they are arrested for DUI, or if a certain standard such as probable cause is met. Violating an implied consent law by refusing a test when it is legally required may expose a driver to separate penalties and may not necessarily prevent a DUI charge.” https://www.justia.com/criminal/drunk-driving-dui-dwi/handling-a-dui-stop/refusing-to-perform-a-breathalyzer-or-provide-a-blood-sample/

[10] Some states now have introduced “no refusal” law. They allow police to immediately contact an on-call judge and get a warrant (via phone or email) to conduct a blood alcohol test. The electronic warrant allows the test to be conducted quickly.: https://www.justia.com/criminal/drunk-driving-dui-dwi/handling-a-dui-stop/refusing-to-perform-a-breathalyzer-or-provide-a-blood-sample/

[11] https://www.americanbar.org/groups/judicial/publications/judicial_division_record_home/highway-to-justice/testing-challenges-no-bac-for-thc/

[12] LAPPA (2022). Drugged Driving: Summary of State Laws https://legislativeanalysis.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Drugged-Driving-Summary-of-State-Laws.pdf LAPPA 2022

[13] https://www.ncsl.org/transportation/drugged-driving-marijuana-impaired-driving

[14] Today, along with Canada and New Zealand, many of the European countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Poland, UK, Spain, Sweden, The Netherlands) and some of the South East Asian countries (South Korea, Vietnam and Hong Kong) are using OFFS.

[15] https://newsroom.aaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/23-1353-TS-Oral-Fluid-Handout-Update.pdf

Moore, C., Lindsey, B., Harper, C. E., & Knudsen, J. R. (2020). Use of Oral Fluid to Detect Drugged Drivers. National Traffic Law Center: Between the Lines, 28(10), 1-11. https://ndaa.org/wp-content/uploads/October-2020-BTL-Oral-Fluid.pdf

[16] https://newsroom.aaa.com/asset/updated-oral-fluid-handout-2024/

[17] https://newsroom.aaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/23-1353-TS-Oral-Fluid-Handout-Update.pdf

[18] Deweese, C. (2023). Oral Fluid Testing to Support DUID Investigations and Improve Drugged Driving Data. Nevada Traffic Safety Summit.

[19] GHSA 2024

[20] Michigan State Police (2021). Oral Fluid Roadside Analysis Pilot Program – Phase II. https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/msp/reports/phase_ii_oral_fluid_report.pdf?rev=911dc2c7042d444eb8918395a2211915

[21] Michigan State Police (2022). Michigan State Police Impaired Driving Investigations. https://public.powerdms.com/MSP1917/documents/1982661

[22] Senjem, D. H. (2022). S.F. No. 2854 – Oral Fluid Roadside Testing Pilot Program. https://assets.senate.mn/summ/bill/2022/0/SF2854/SF%202854%20summary.pdf

[23] https://www.mprnews.org/story/2024/01/05/coming-soon-to-minnesota-roadways-oral-tests-for-marijuana-other-drug-use-by-drivers

[24] https://www.tsrinjurylaw.com/blog/police-to-use-oral-tests-for-marijuana-other-drugs/

[25] https://www.in.gov/cji/traffic-safety/impaired-driving/roadside-oral-fluid-program/

[26] https://events.in.gov/event/police_in_lake_county_equipped_with_new_device_to_combat_drugged_driving

[27] https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/indiana-oral-fluid-testing-impaired-drivers/

[28] https://adfs.alabama.gov/services/tox/toxicology-oral-testing-program

[29] Harper, C. E., Hudson, J. S., Tidwell, K., Boswell, R., Yong, H. L., & Maxwell, A. J. (2023). Implementation of the first comprehensive state oral fluid drug testing program for roadside screening and laboratory testing in DUID cases-A 5-year review. J Anal Toxicol, 47(8), 694-702. https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkad051

[30] https://adfs.alabama.gov/services/tox/toxicology-oral-testing-program

[31] https://visionzero.nd.gov/news/LawEnforcementimplementingroadsidetooltocombatdruggeddrivers/

[32] https://vtdigger.org/2020/02/27/house-rejects-warrantless-saliva-tests-defying-scotts-terms-for-legal-pot-market/

[33] Logan, B. K., & Mohr, A. L. A. (2015). Final Report: Vermont Oral Fluid Drug Testing Study 2015. The Center for Forensic Science Research and Education. https://legislature.vermont.gov/Documents/2018/WorkGroups/House%20Judiciary/Bills/H.237/H.237~Trish%20Conti~VT%20Oral%20Fluid%20Drug%20Testing%20Study%202015~2-23-2018.pdf

[34] A recent NHTSA evaluation reviewed five such devices for their accuracy, reliability, performance, susceptibility to interference, and resistance to extreme conditions. (See: Buzby, D., Mohr, A. L. A., Logan, B. K., & Lothridge, K. L. (2021). Evaluation of On-Site Oral Fluid Drug Screening Technology. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/54911)

[35] https://nasid.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/R.org_5085_Data-Checklist_12_DEC-13_2024.pdf